The Farnese Hercules is among the most celebrated sculptures of antiquity. Since its discovery, its reputation has continued to expand. From the moment of its unearthing, it has inspired and stimulated scholarly research by artists, art historians, and archaeologists, as well as serving as a symbolic representation of strength and athletic prowess within the European cultural sphere. In the modern era, numerous replicas, copies, and reproductions have rendered the Farnese Hercules an aesthetic icon capable of reflecting evolving artistic preferences and conveying new interpretations of ancient statuary in the current context.

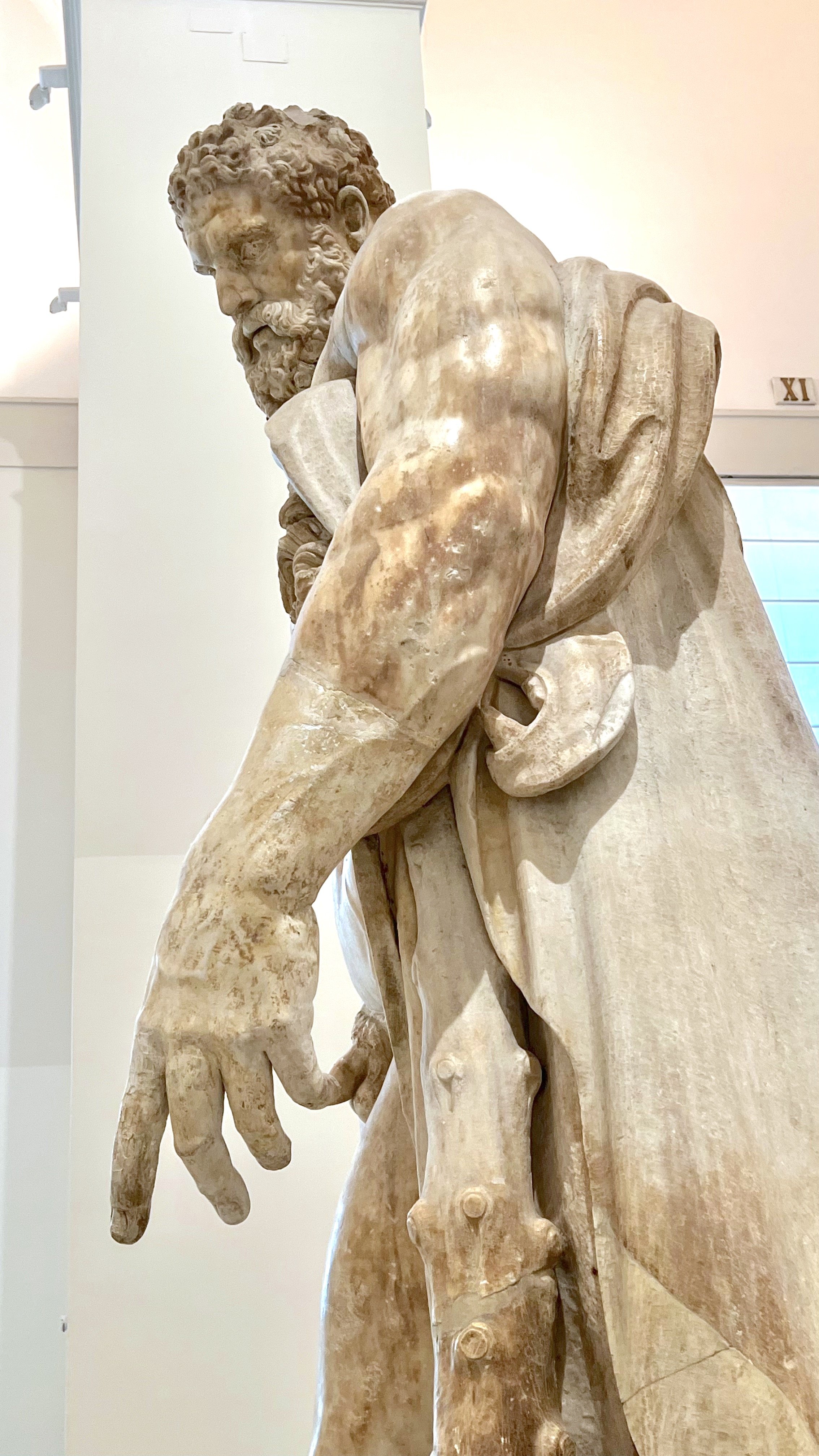

The Farnese Hercules is a marble sculpture that stands 317 centimetres tall and is displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. It originates from the late 2nd to early 3rd century AD.

The sculpture is a copy of a Greek bronze original, dated to the second half of the 4th century BC, most likely attributable to Lysippus or his workshop. It depicts one of the most renowned representations of Hercules resting after overcoming the legendary trials imposed by the gods.

The hero appears fatigued and contemplative following yet another arduous task assigned by his cousin Eurystheus. The fruit he holds in his right hand, carried behind his back, suggests that this scene depicts the conquest of the apples in the Garden of the Hesperides.

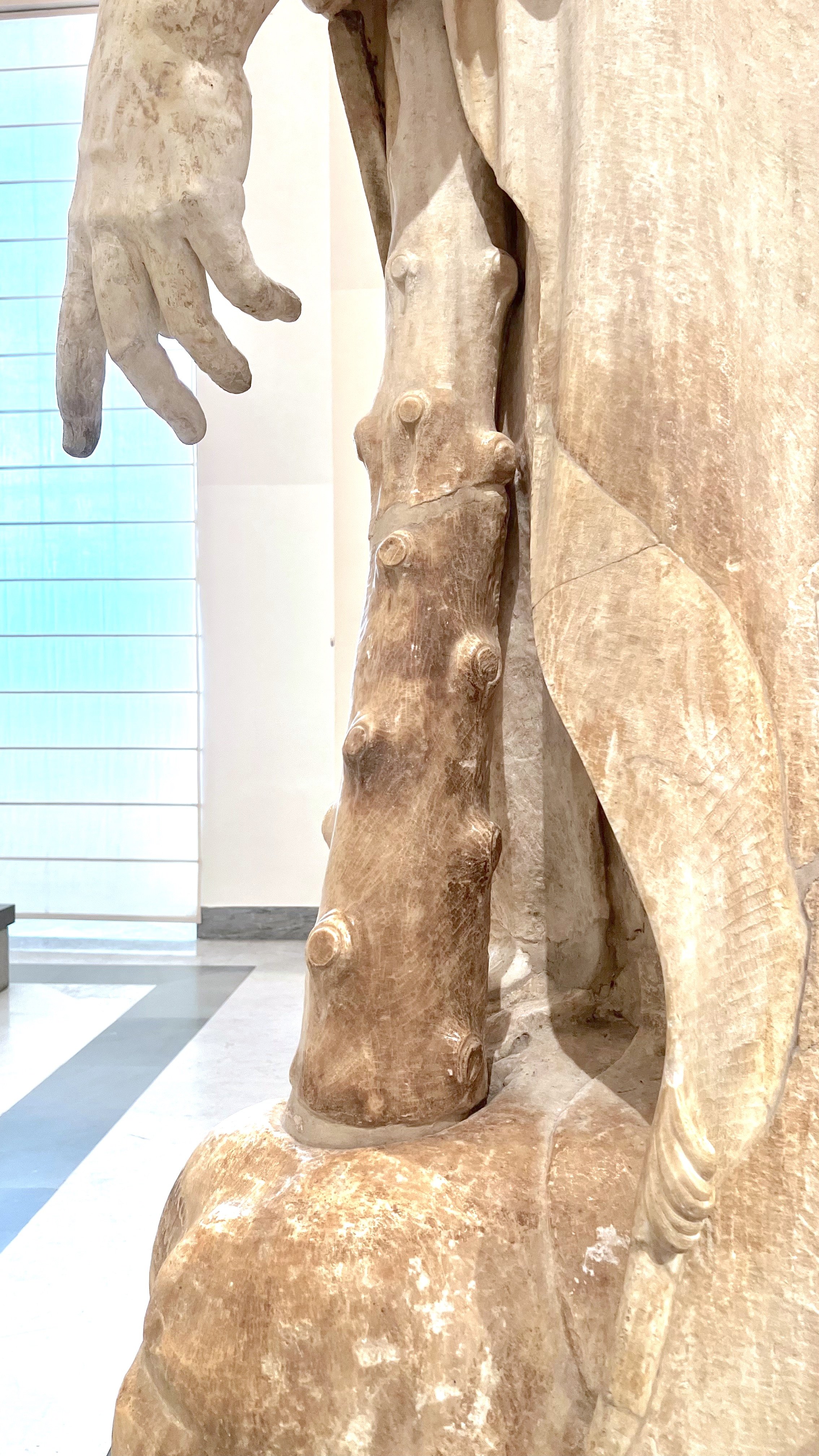

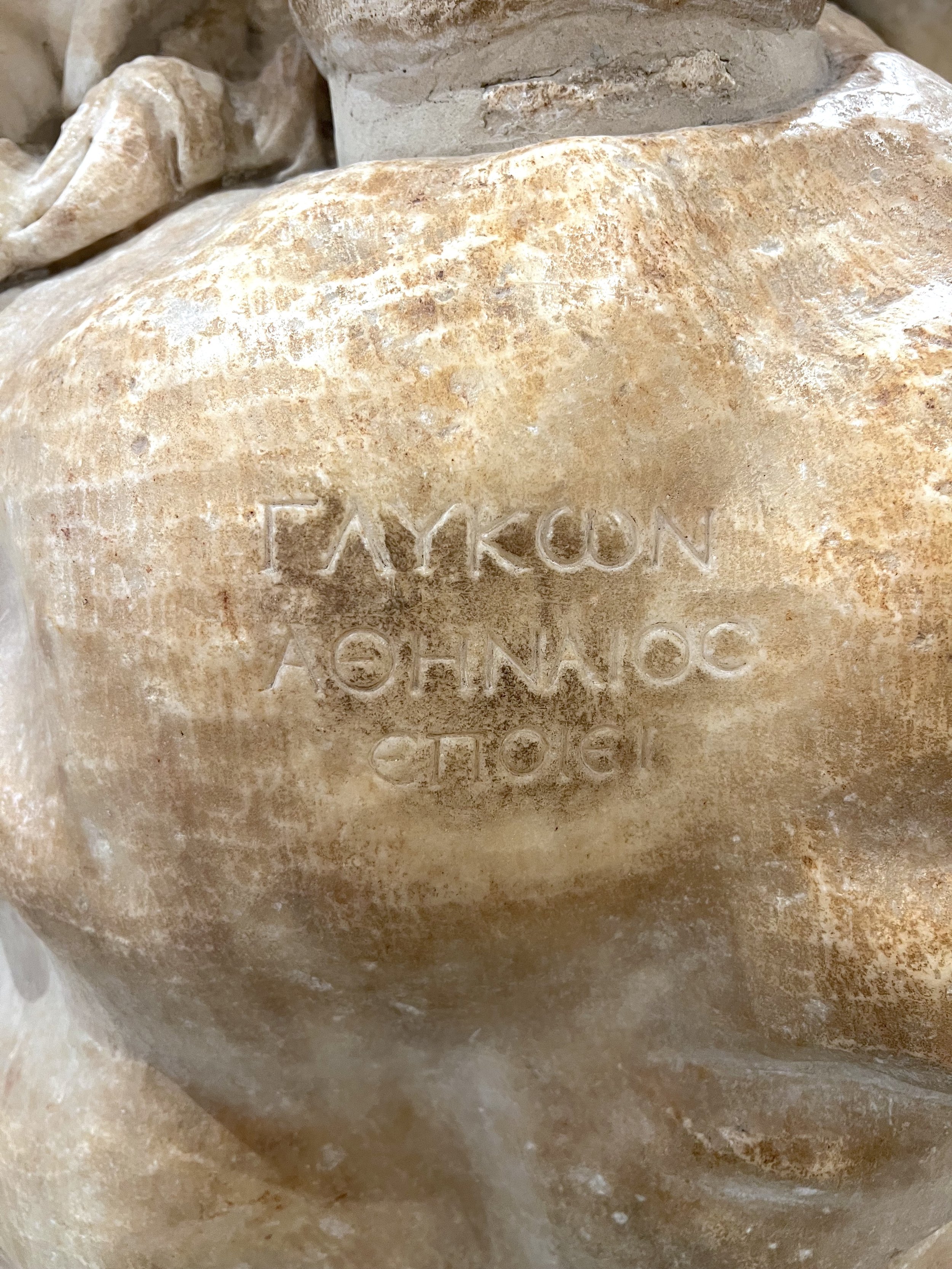

The hero has laid down his club and the leonteia, the skin of the gigantic Nemean lion killed during the first labour. An inscription in Greek, bearing the sculptor's signature, is engraved on the rock base: "ΓΛΥΚΩΝ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ ΕΠΟΙΕΆ," Glycon athenaios epoiei, indicating the name of the Athenian copyist Glycon. The statue was discovered in 1545 (although its head was missing, which was rediscovered and replaced in 1563) within the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. According to Antonio da Sangallo, it was located in a passageway between the frigidarium (cold-water pools) and the north gymnasium. It was found alongside a similar, albeit inferior-quality, statue identified as the Latin Hercules, now preserved in the Royal Palace of Caserta.

It is believed that the two statues are part of a set of twelve large Hercules statues, similar to his twelve labours, displayed inside the Baths. These statues became the property of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and were added to his collection. At Michelangelo's request, both sculptures were placed in the courtyard of Palazzo Farnese, under the arches of the portico facing the garden.

The Resting Hercules was later moved to the Hall of Hercules in Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Charles of Bourbon, son of Elisabetta Farnese, inherited the collection from his mother. In 1787, all the ancient artworks were relocated to the Royal Palace of Capodimonte in Naples, and the Resting Hercules was subsequently moved to the Royal Palace of Naples, where it still resides. Among the Lysippean works depicting the demigod, the Resting Hercules is the most famous, mainly due to the recognition it gained after its discovery.

Heracles's constant and persistent presence in Lysippos's sculptures can be understood through the sculptor's intense focus on symmetry. Lysippos aimed to develop a portraiture style that highlighted athleticism and the geometric proportions of the human body, while also capturing the subject's deep psychological and emotional aspects. Heracles, a hero described in texts as a demigod with strong muscles yet psychologically troubled, was an ideal subject for Lysippos's art. In this sculpture, Lysippos chose to depict Heracles paused, a decision that led to an innovative work where the study of musculature becomes secondary to expressing a psychological moment—delicate, intense, and human. The overall figure is perfectly proportioned, including the head with its short, curly hair and thick beard, which matches the figure's anatomical structure.

Heracles' compositional design contrasts the relaxed left side with the tense right, with tension emphasised by his grip on the right hand. The club, resting on the rock, not only provides stability and balance for the sculpture but also supports the figure's left-handed imbalance, even though the right leg bears the weight.

The sculpture symbolises the final stage of the Twelve Labours, depicting the hero resting after completing the eleventh task: retrieving the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides. These nymphs, daughters of Titan Atlas, along with the serpent Ladon, guarded the tree with the golden fruit given to Hera by Gaia during her wedding in the Hyperborean region.

To retrieve the apples, Heracles asked Atlas for help, who agreed to gather the fruit in exchange for holding up the sky temporarily. After obtaining the apples, Atlas returned to his post, but, no longer bound by Zeus's sentence, he did not keep his promise. Using a stratagem, Heracles tricked Atlas into returning to his duty.

A close examination of the hero's face reveals signs of fatigue alongside a hint of melancholy—his posture links to the final, twelfth labour. The figure exudes a sense of calm, as if the work is complete, but also an awareness that more challenges lie ahead, as shown by his left leg, which is moving forward —a step toward the gates of Hades. Here, Heracles must capture Cerberus, the three-headed guard of the underworld, alive.

The Twelve Labours symbolise humanity's struggle against nature, seen as a form of divine manifestation in its wildest and most fearsome aspect. Heracles embodies courage, moral discipline, strength, cunning, and physical effort. He is also considered the founder of the Olympic Games and a symbol of salvation and human redemption from divine cruelty. This Greek hero was highly venerated in antiquity, inspiring numerous artistic representations across different periods and media. The sculpture examined is a prime example of a popular ancient type: a hero depicted in a moment of repose and introspection, appearing natural and human, not at his most potent.

Via

Città, Provincia, CAP

Numero di telefono

Esplorando l'antichità classica.

Your Custom Text Here