The Farnese Hercules is among the most celebrated sculptures from the ancient world. From its discovery to the present day, its popularity has remained steady. Since its finding, it has inspired and interested artists, art historians, and archaeologists, while also serving as a symbol of strength and athleticism in European culture. Over time, replicas and reproductions of all kinds have made the Farnese Hercules an icon of aesthetic value, reflecting changes in artistic taste and conveying new meanings assigned to ancient statuary in the modern era.

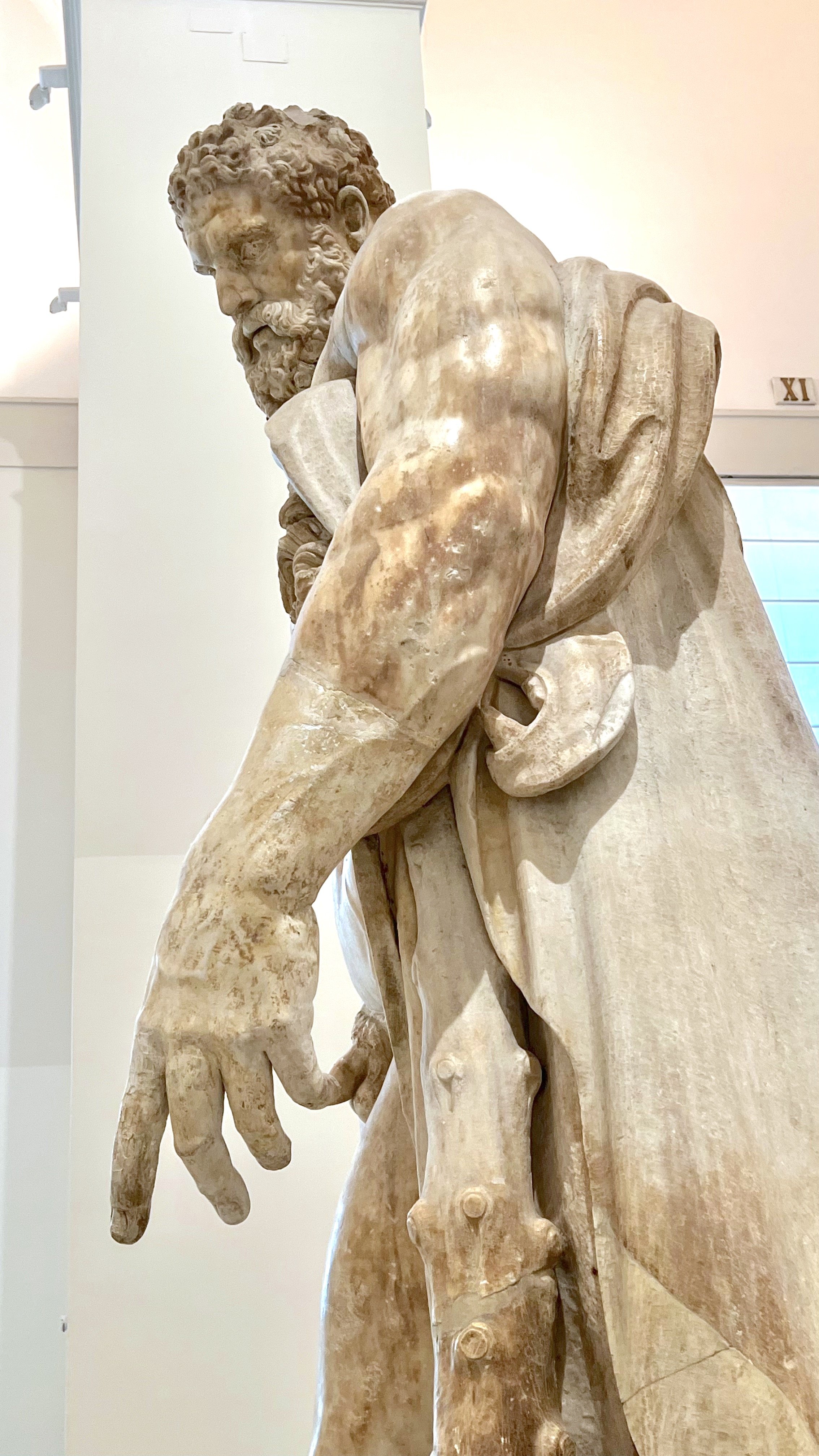

The Farnese Hercules is a 317 cm tall white marble statue, displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, dating from the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD. It is a copy of a Greek bronze original from the second half of the 4th century BC, possibly created by Lysippus or his workshop. It illustrates one of the most well-known versions of Hercules resting after completing his famous labours.

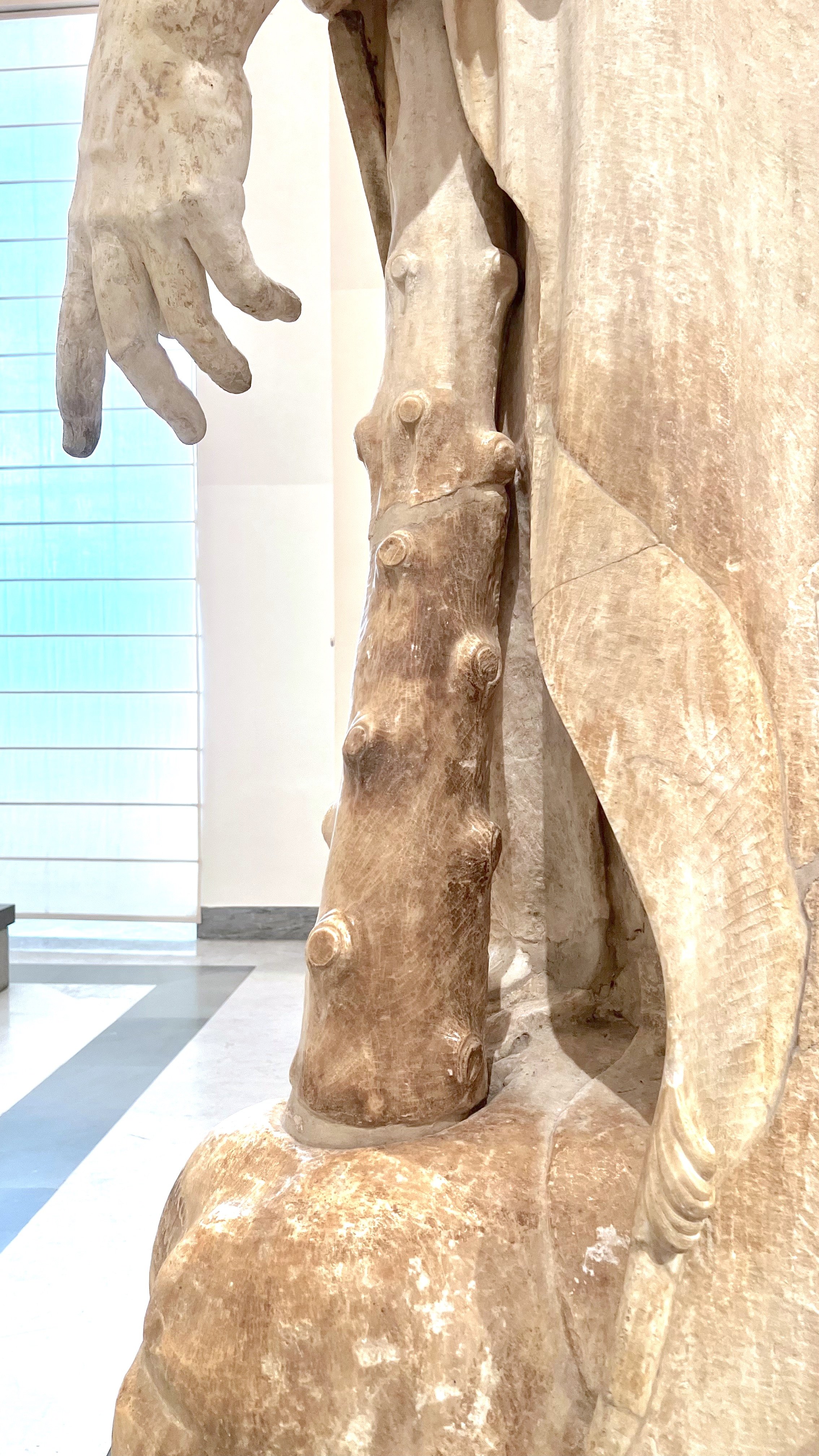

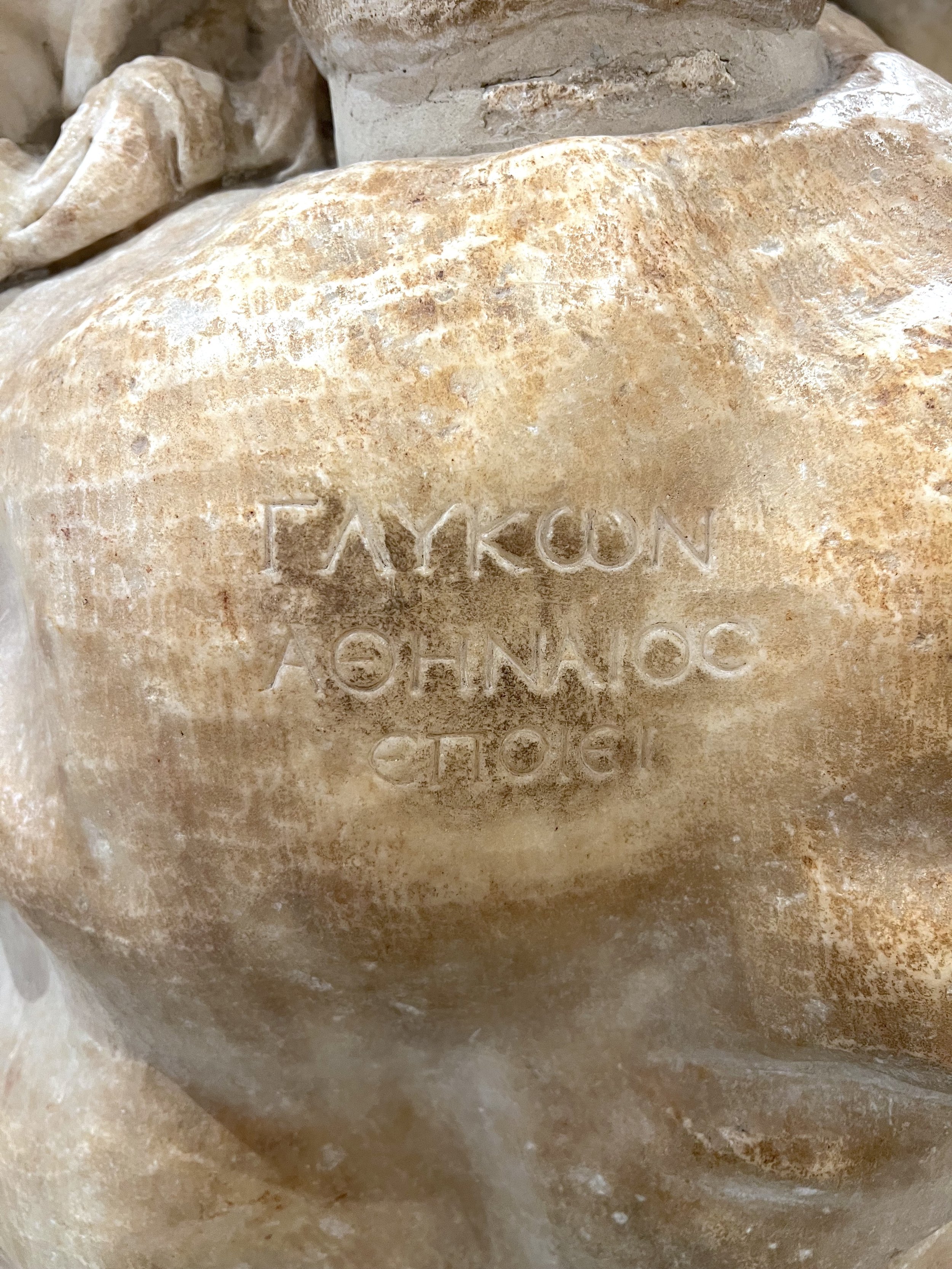

The hero appears tired and contemplative after yet another task imposed by his cousin Eurystheus. The fruit in his right hand, held behind his back, suggests he is trying to acquire the apples from the Garden of the Hesperides. The rock indicates the scene from the myth. The hero has placed his club and the leonteia, the skin of the giant Nemean lion slain in the first labour, on the rock. An inscription in Greek with the sculptor's signature is visible on the base of the rock: "ΓΛΥΚΩΝ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ ΕΠΟΙΕΙ", Glycon Athenaios epoiei, the name of the Athenian copyist Glycon.

The statue was discovered in 1545 (although missing its head, which was found and replaced in 1563) inside the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. According to Antonio da Sangallo's testimony, it was specifically located in a passageway between the frigidarium (cold-water pools) and the north gymnasium. It was found alongside a similar, lesser-quality statue known as the Latin Hercules, now in the Royal Palace of Caserta. It has been theorised that the two statues were part of a set of twelve large Hercules statues, akin to his twelve labours, displayed within the Baths.

The statues became the property of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and were added to his collection. At Michelangelo's request, both sculptures were placed in the courtyard of Palazzo Farnese, under the arches of the portico overlooking the garden. The Resting Hercules later found its way into the Hall of Hercules, also in Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Charles of Bourbon, son of Elisabetta Farnese, inherited the collection from his mother. In 1787, all the ancient artworks were transferred to the Royal Palace of Capodimonte in Naples, then to the Palazzo del Real Museo. Finally, the Resting Hercules was moved to the Archaeological Museum of Naples, where it remains today. Of the Lysippoan works depicting the demigod, the Resting Hercules is unquestionably the most famous, owing to the fame it gained following its discovery.

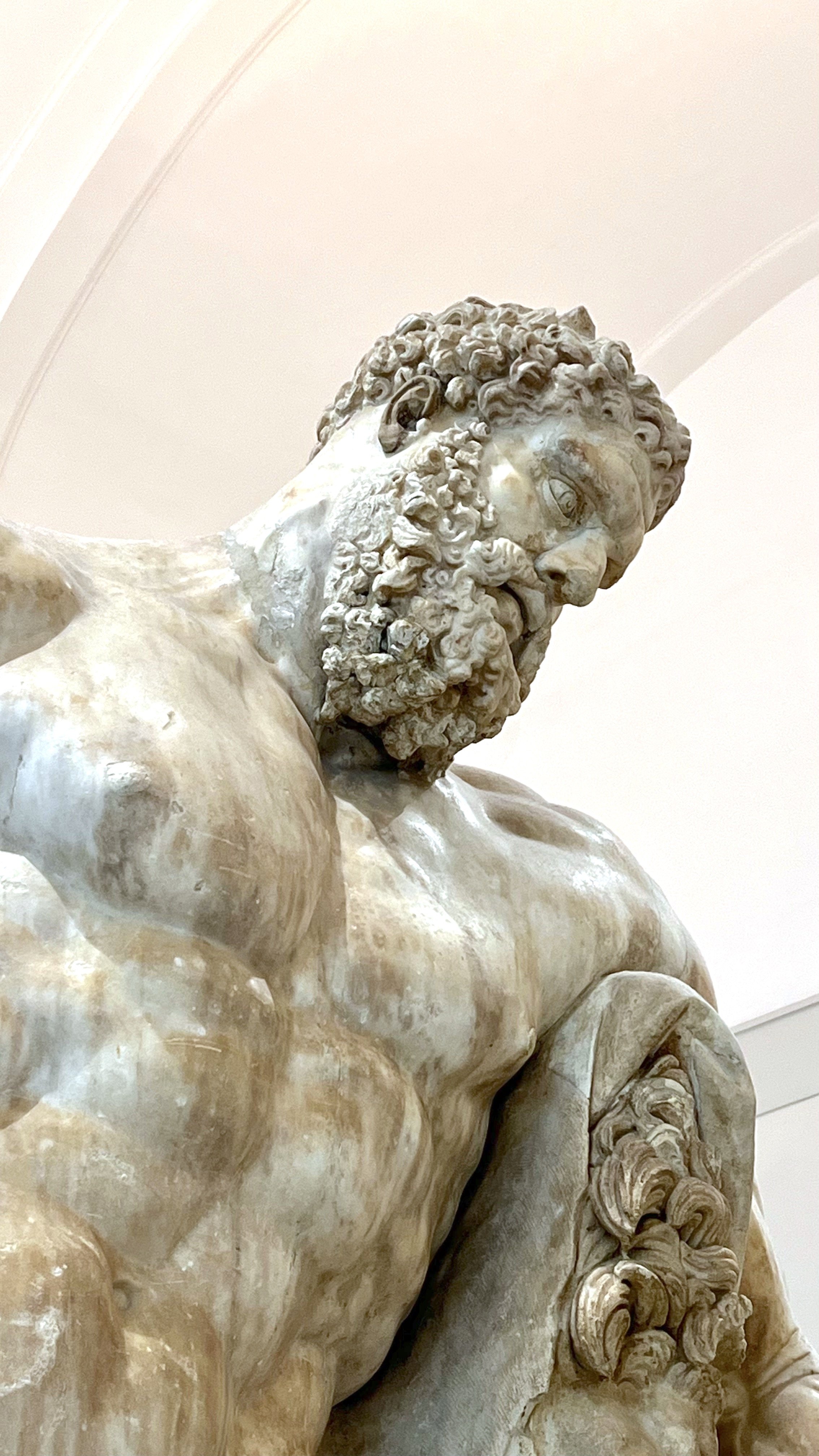

The constant presence of Hercules in Lysippos's sculptures can be attributed to the sculptor's relentless pursuit of symmetry and balance. Lysippos aimed to create portraiture that emphasised the athleticism and appropriate geometric proportions of the human body while also capturing the intense psychological and emotional nuances of the subject. A hero like Heracles, described in literary sources as a demigod with strong, powerful muscles yet psychologically conflicted, ideally suited Lysippos's artistic aims. In this work, Lysippos depicts Heracles in a moment of pause, allowing him to produce a new piece where the study of formidable musculature becomes secondary to expressing the psychological state—delicate, intense, and human. The figure, as a whole, is perfectly proportioned, with harmony between its different parts, including the head, which features hair defined by short locks and a thick beard, aligning well with the body's structure. The composition of Heracles contrasts the relaxed left side with the tense right, highlighted by focused tension in the grip of the right hand. The club resting on the rock is essential and functional, providing support for the figure's left-leaning stance, even though the right leg serves as the supporting limb.

The sculpture thus evokes the final phase of the Dodekathlon (the 12 feats), showing the hero in a moment of repose after completing his eleventh labour: having managed to capture the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides. These nymphs, daughters of the Titan Atlas and the serpent Ladon, were tasked with guarding the tree bearing golden fruit that Gaia had given to Hera for her wedding in the land of the Hyperboreans.

To obtain the apples, Heracles asked Atlas for help, who offered to gather them for him if he would hold up the vault of Heaven in his stead. Heracles agreed, and Atlas returned with the apples, but, freed from the burden of the sentence inflicted on him by Zeus, he did not keep his promise, and only through subterfuge did the hero manage to restore Atlas to his place. Suppose one carefully observes the hero's face, which, in addition to showing fatigue, also betrays a feeling of melancholy, and the pose of his body. In that case, one notices a connection with the twelfth and final labour. Indeed, the figure conveys a sense of repose for the labour completed, but also the awareness that the deeds are not over, represented by the left leg posed in a walking motion, an allusion to the approach of the gates of Hades, where Heracles must capture alive the three-headed dog Cerberus, guardian of the underworld. The Twelve Labours have always symbolised the clash between man and nature, an expression of divinity in its most savage and terrifying form. Heracles is considered a symbol of courage, moral rigour, strength combined with cunning, and physical activity (according to tradition, he is the founder of the Olympic Games), as well as a figure representing humanity's salvation and redemption from divine cruelty. The fascinating figure of the Greek hero was highly venerated in antiquity, to the extent that the most significant artists repeatedly reproduced it on every medium and through the most diverse iconographies. The sculpture in question is undoubtedly one of the finest copies of a highly prized statuary type in the ancient world: that of the hero captured in a moment of repose and reflection, entirely human and natural, and not at the height of his strength.